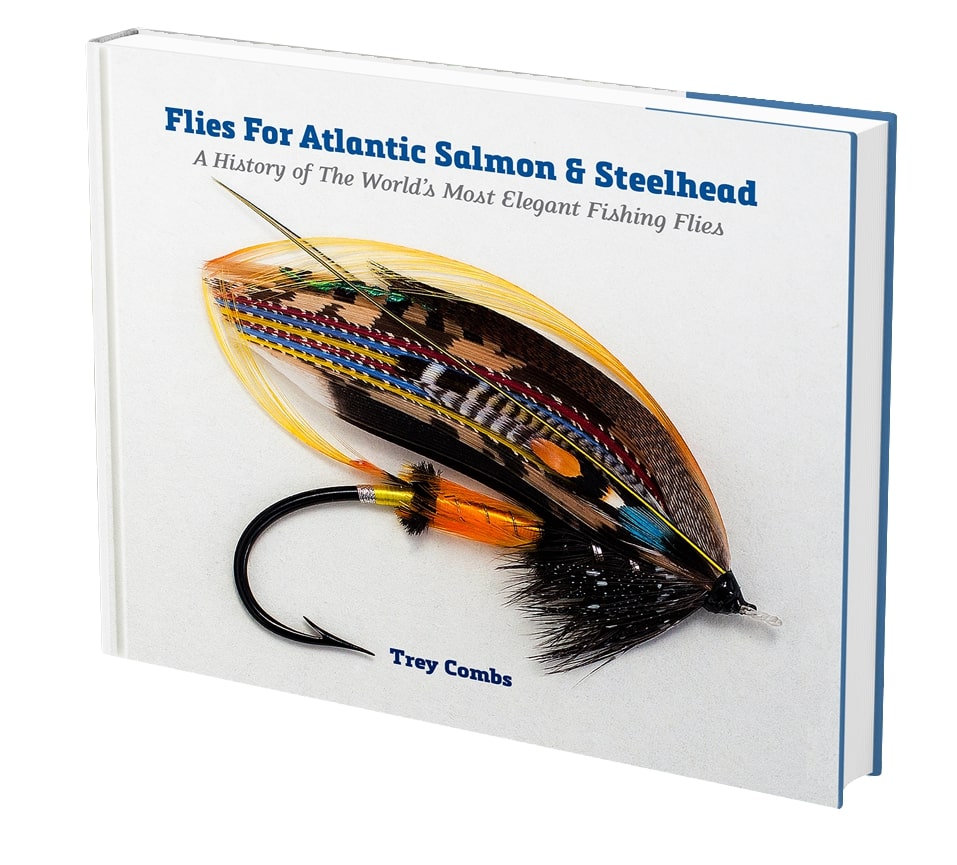

Trey Combs’ latest book, Flies For Atlantic Salmon & Steelhead, is vintage Combs: it’s a must read. At first glance, the book is an instant eye-catcher. The design, imagery and presentation are stunning. In this case, it falls in line with books that are published by Wild River Press. It’s classic Tom Pero. So, there’s that.

Beyond that, Combs’ book is a collection of a who’s who in the steelhead and Atlantic salmon fly-fishing community. There are too many to list, but rest assured you will recognize many of the people who either contributed a photo or lent their pen. Moreover, Combs masterly weaves in the history of each fly, it’s fly-tying recipes, evolution of techniques, fly rods and flies. There are notable chapters on modern-day fly tiers including John Shewey, Dave McNeese, Frank Amato, Jay Nicholas and Brian Silvey (among others). I was particularly impressed with the chapter on the history of steelhead and how it came to get its name: Oncorhynchus mykiss. It reinforces ideas many of us already know, but I learned more from that chapter than I thought I previously knew. Talk about a history lesson.

By Pat Hoglund

I also enjoyed reading about how John S. Benn came from Ireland and created steelhead flies for California. Primarily focused on the Eel River, Combs delivers another chapter that steelhead anglers will find interesting, captivating and educational. Also included is a memorable chapter on Zane Grey and his love affair of fly fishing for steelhead on the North Umpqua and Rogue rivers.

As an emerging author, Combs published his first book in 1971, The Steelhead Trout (Salmon Trout Steelheader). He followed that with Steelhead Fly Fishing and Flies (Salmon Trout Steelheader, 1976), which the steelhead fly-fishing community called the “steelheader’s bible.” It remained in print for 30 years. His magnus opus, Steelhead Fly Fishing (Lyons and Burford, 1991) propelled him to the top of the fly-fishing literary world. He’s published numerous other books, but it can be argued that his recently released book is one for the ages. Weighing six pounds, one ounce, this is more than a coffee table book. It’s a book that begs to be read.

What follows are questions and answers I posed to Combs in relation to his book and his fly-fishing career. Many of the answers have been edited for brevity.

I also enjoyed reading about how John S. Benn came from Ireland and created steelhead flies for California. Primarily focused on the Eel River, Combs delivers another chapter that steelhead anglers will find interesting, captivating and educational. Also included is a memorable chapter on Zane Grey and his love affair of fly fishing for steelhead on the North Umpqua and Rogue rivers.

As an emerging author, Combs published his first book in 1971, The Steelhead Trout (Salmon Trout Steelheader). He followed that with Steelhead Fly Fishing and Flies (Salmon Trout Steelheader, 1976), which the steelhead fly-fishing community called the “steelheader’s bible.” It remained in print for 30 years. His magnus opus, Steelhead Fly Fishing (Lyons and Burford, 1991) propelled him to the top of the fly-fishing literary world. He’s published numerous other books, but it can be argued that his recently released book is one for the ages. Weighing six pounds, one ounce, this is more than a coffee table book. It’s a book that begs to be read.

What follows are questions and answers I posed to Combs in relation to his book and his fly-fishing career. Many of the answers have been edited for brevity.

Q&A with Trey Combs

Hoglund: When did you start writing Flies For Atlantic Salmon & Steelhead, and when did you finish with your first draft?

Combs: I began researching and writing ideas in 2017. I’d contacted Tom and discussed the overall trajectory of the book. He wanted me to concentrate on the flies and I wanted to include something about each of the four great watersheds, south to north, beginning with the Sacramento-San Joaquin. I’d spent the previous year working just on this. Thankfully, Tom stripped this out and gave the book needed direction. Early in 2022, I printed out the book, filled it chapter by chapter in several notebooks and sent it to Tom as a test run. He sent it back with a request to add in the history of the Victorian era’s complex Atlantic salmon flies, a project that took five to six very intense months. Tom liked it; I felt this this was among the best parts of the book. This history kind of balanced the steelhead chapters related to John Benn.

Take a guess: how many hours did it take to write it?

Too many! I’d guess over 5,000 hours.

If this were a novel, how you describe the plot?

Two different plot lines brought together by the flies we tie to attract them; identical flies will attract both different species. That’s the only thing the two species have in common. If asked what’s the difference between the two fish, I can ask back, What’s the difference between rainbows and browns?

This book is rich in history. Briefly explain your research process?

I was ill for nine months and unable to effectively write. I did intense research by finding the myriad of backstories online and printing them off. When I got back to the writing my progress moved along more quickly. I’d read all the documents until I could tell a story about the event.

Who were/are your mentors in the fly-fishing community?

When I came from Whittier College to Tacoma, Washington, I joined the Puget Sound Fly Fishing Club. My mentor was Morrie Kenton, and his favorite dry fly, the Royal Buck, became mine as well. Later on, Frank Amato was my mentor. When Frank published Steelhead Fly Fishing and Flies in 1976, the book represented the first effort to describe the fly-fishing culture for steelhead. I didn’t initially identify the book in such a grand manner, but over time—Frank kept the book going for 30 years—people came to regard it in that fashion.

How has your writing changed from your first book in 1971 to today?

The big change occurred when writing Steelhead Fly Fishing in 1991, because I had both a computer and my girlfriend, a skilled editor. For the first time I could labor over each sentence, make changes, print the result, and edit it still more. The chapter on the Rogue River and Zane Grey was edited over and over and printed out 11 times. Nick Lyons sent the manuscript to a proofreader who was the wife of a famous publisher, and she changed one word in the 200,000 word manuscript. That computer, crude by today’s standards, made all the difference.

What chapter, or section, was your favorite to write?

My favorite to write was your favorite to read, the steelhead’s taxonomic history. I knew the subject but including the explanation why today we give steelhead the species name mykiss instead of gairdneri took a lot of digging. But being able to mesh all this by reading documents by Steller and his Russian subordinate, Stephen Krasheninikov, was rewarding, doubly so when elements of this history took place on the Zhupanova, a Kamchatka river I fished and took stunning rainbows to 31 inches and at least 11 pounds.

Whether it was Zane Grey, Syd Glasso, Dave McNeese, Frank Amato or Jeff Cottrell, you write about some of the most influential Atlantic salmon and steelhead fishermen in the world.

I’ve been extremely fortunate to have known so many well-known fly fishers. When I began writing about flies, I eagerly listened to persons tell me about their flies and their experiences. Amazingly, back in the late 1960s, no one had ever asked them such questions. I immediately learned that this was a small community of anglers, and they knew each other.

In writing the Preface—the history of steelhead— what did you learn?

Hard to believe but when writing Steelhead Fly Fishing and Flies, the steelhead was Salmo gairdneri, and I made the most of that. The aristocrat of all game fish, the Atlantic salmon, was a close relative to the steelhead. But even back them, I didn’t find much in common between brown and rainbow trout. I said that a lot when fishing Montana’s Big Hole River. I think I’ve spent generations trying to pull steelhead toward how the public perceives Atlantic salmon. When I’d finally enjoyed casting for Atlantic salmon in four countries, I was more determined than ever to move the steelhead to that lofty level of passionate recognition of Atlantic salmon.

Whether it’s the history of Atlantic salmon and steelhead, the rivers they swim, the flies used to pursue them, or the influential people, the amount of information in your book is staggering.

I failed to appreciate the volume of the history getting documented until Tom and I were doing the overall editing, and not concentrating on a single chapter—easy then to get tunnel vision. But my reaction to the finished product as a book astounded me, the book having a “Wow!” factor. Having a lot of contacts, and having persons who had copy of Steelhead Fly Fishing, helped in having them identify with the project and their willingness to contribute. Many of the northern Europeans in camp in Norway had a copy of that book.

You’ve fished all over the world, Scotland, North America, Russia, what is your most memorable fishing trip?

Honestly, can’t think of just one. I’ve experienced some epic struggles with huge saltwater gamefish. I’ve described elsewhere about the mystique Norwegian salmon have because you can hook a fish so large that grassing it is unlikely. Favorite steelhead: Potato Patch Run on the Kispiox. Another memorable trip was on Russia’s Yokanga River during the dusk of night. I had a wonderful time hooking numerous Atlantic salmon on a micro Sunray Shadow. I thought the largest would have weighed 30+ pounds. The steelhead river I’d most like to fish while I’m still upright would be the lower Dean River.

Looking back on your career, what is one thing that you most appreciate?

No matter how many steelhead or salmon I hook, the take never fails to shock me.

List your top three Atlantic salmon flies and your top three steelhead flies?

Atlantic salmon: Sunray Shadow, Micro Sunray w/pearl Flashabou; Sunray variants such as black over dark blue. I’d also pick Templedog dressings with black over green over white or yellow. Steelhead: Night Dancer and the same fly dressed as a Spey fly. (Preference for tying it sparsely on a Waddington shank.) SteelFlash Blue, SteelFlash purple—also tied on Waddington shanks.

How many steelhead have you caught in your lifetime?

Hundreds if counting steelhead and not “half-pounder” grilse.

Fishing the Klamath with a 4-weight for steelhead averaging 20 inches is fantastic fishing. Imagine if a run of these fish took place in Montana. It would be called the finest Blue Ribbon Trout Stream in the world!

How many Atlantic salmon have you caught in your lifetime?

No more than 50 including all grilse.

If forced to choose, which is your favorite: steelhead or Atlantic salmon?

Honestly, this is impossible to answer without qualifications. Please bear with me, but I’d like to belabor my answer. When I fished in Norway in 2019, I discovered that every fly fisher of some experience had stories to tell about a salmon of at least 15 kilos, or more frequently one of over 20 kilos, that had been hooked but eventually lost. I found these salmon to be very strong and a fresh fish of such size would be difficult to land without a boat. Their experiences weren’t limited to famous big salmon rivers like the Gaula or Alta, but on almost any river. This was much of the mystique, the romance, of rivers that possess such salmon of legend. In terms of how the two species fight the rod when hooked, I found that grilse to grilse, there’s a similarity, but adult to adult depends whether we’re talking about winter or summer, and with steelhead, male or female. And whether fresh-run and sexually immature (a colored up, sexually mature male).

I don’t think any salmonid can match the Skeena’s summer-run female steelhead of 12 to 15 pounds. They grab a fly, turn, and race down the pool and over the break and down into the next pool in a few seconds. No Atlantic salmon does that so quickly. But salmon will marshal their strength more economically, and thus fight longer, often much longer. A buck steelhead of 25 pounds when entering the Skeena at Prince Rupert in September weighs 18 pounds in October and may act out of gas when hooked. The buck will hang around until the last angler and female steelhead have left and then perhaps drift downriver and a few may even reach saltwater, but they’ll never return. These bucks, three-year ocean fish, are one and done.

As you know, steelhead and Atlantic salmon take the fly differently, the salmon more deliberate and sucking in the fly so that it can be outside the gills. This slow, deliberate take is what greased line fishing was all about. Dropping a loop when a summer-run steelhead takes your fly is idiocy, doubly so when fishing for winter-run steelhead. These species are so different even though they’ll take the same fly. Anyone challenging this needs to ask themselves how similar rainbow trout are to brown trout.

If you had one week to live, what river would you fish?

Norway’s Alta in late June.

What rod would you use?

My 13-foot, 8-weight Burkheimer, but longer and more powerful rods are in common use on the Alta, not because these largest salmon in the world are more common here than on any other river, but to better command the big water. You might find this interesting. When in Norway and fishing the Reisa, there was a huge two-sided rod rack just off the canvas-covered dining area. Half of all the rods racked up were Burkheimers.

List the flies you’d bring.

Tubes, starting with the Sunray Shadow and some variants. But … a popular fly on this incredible river is the Dirty Banana tied Templedog style.

Order your very own copy of Flies for Atlantic Salmon and Steelhead here.