On a remote finger of Iceland’s green and rocky Westfjords sits the fishing village of Bíldudalur, home to The Icelandic Sea Monster Museum.

Arnarfjörður, the inlet cradling this community of 243, is Iceland’s heartland for sea monster sightings. The museum houses dioramas showcasing sea monsters in their natural habitats, atmospherically lit to evoke the eerie depths of the ocean floor or the shadowed beach at night. An interactive map meticulously charts eyewitness reports of monster sightings throughout the region. Speak of the museum’s exhibits as mere folklore, and you might invite a passionate defense from a local, eager to recount their own encounters with one of the local fabled beasts—the fjörulalli beaver-wolf, the fearsome merman hafmaður, the shell-armored and sharp-clawed skeljaskrímsli, or the dreaded razor-toothed faxaskrímsli seahorse. While the sea monsters of Arnarfjörður may seem like legend, the true horrors plaguing Icelandic waters today are man-made—genetically engineered, farm-raised salmon.

BY Sarah Grigg for The Drift by Eleven Angling

Farmed salmon raised in open-net pens exhibit traits as gruesome as their folkloric counterparts—bodies riddled with crustaceous lice, melting flesh, shredded fins, crooked spines, and a host of other disturbing maladies. After more than a decade of allowing Norwegian commercial aquaculture operations to raise “franken-salmon” along pristine coastlines, wild Atlantic salmon now face potential extinction in Icelandic waterways. The topic has generated debate among the Icelandic public (and international conservation community) as to what the fate of farmed fish and wild Atlantic salmon in Iceland will be.

In spite of the country’s contemporary global reputation as a pristine ecotourism destination, Icelanders have at times participated in the same questionable natural resources management practices as many other societies. Drive across Iceland today and you’ll be hard pressed to spot a tree. That’s because Viking settlers clear-cut forests for charcoal, tools, houses, and ships. Reforestation was impeded by the harsh environment and the introduction of sheep grazing, which inhibits growth. Like the vanished walrus (hunted for ivory) or the disappeared great auk (hunted for consumption), the wild Atlantic salmon now teeters on the brink of extinction in Iceland—another casualty of unsustainable practices.

As a keystone species, salmon have a ripple effect on the people and wildlife that depend on them. Globally, the numbers of wild Atlantic salmon have dropped from 8–10 million in the 1970s to 3–4 million today. Twenty years ago, a million salmon spawned in Norway’s rivers. Today scientists estimate 500,000 fish now spawn there annually. In 2023, Scotland designated Atlantic salmon an endangered species.

“Iceland is one of the last great places for wild Atlantic salmon,” said Elvar Friðriksson, program director of the North Atlantic Salmon Fund (NASF), a group dedicated to conserving the species across its historic range in Iceland and Greenland, with affiliate organizations in nine countries. “We have an incredible number of rivers for a small island and we have good trout and salmon fishing. We are among the few places left with these fisheries and we need to start making smart choices today. To most people, Atlantic salmon is a piece of flesh in a supermarket. They don’t realize what’s behind this product.”

FAXASKRIMSLI

(SEAHORSE MONSTER)

Like other sea monsters in Icelandic folklore, these creature were seen as harbingers of doom or dangerous natural forces. the appearance of the seahorse’s mane at the water’s surface was believed to preceed storms, shipwrecks, or natural disasters. Sea monsters embodied fear of the unknown, particularly the ocean which was crucial for fishing and travel but also a source of death and destruction.

The species has arrived at its current predicament through a combination of biological predisposition and policy missteps of the 20th and 21st centuries. The species first became a conservation target in Iceland in the mid-1980s when commercial fishing escalated.

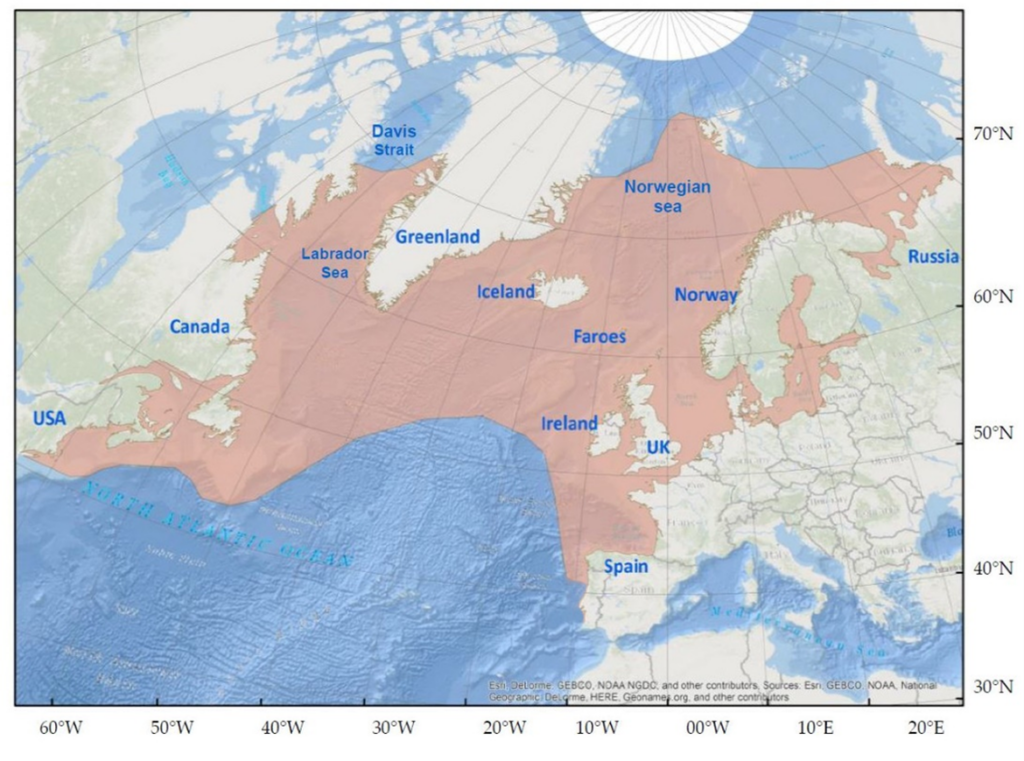

Atlantic salmon have roamed the North Atlantic since the end of the last Ice Age, roughly 10,000 years ago. Their rivers of origin stretch from Maine to Iceland, and from the Iberian Peninsula to Russia. Each year, fish from more than 2,000 river systems return to the same two summer feeding grounds, gathering either off Greenland’s west coast or around the Faroe Islands. Through the 19th and 20th centuries, demand for salmon increased and these feeding grounds became hot spots for commercial fishing. Nets from Greenlandic, Icelandic, and Faroese boats were thrown indiscriminately, meaning an entire river’s salmon stock could theoretically be wiped out with just one net. Over 2,500 tons of salmon were pulled from Greenlandic waters between 1988 and 1990 alone. High seas fishing, combined with heavy net fishing in Iceland’s glacial rivers, impacted the entire Atlantic salmon population. By the 1970s and into the 1980s, countries on both sides of the Atlantic reported poor returns on spawning rivers.

Some suspect the increased demand was driven by new sushi practices. Traditional Japanese sushi making did not incorporate salmon, as it was not part of the country’s diet or immediate marine ecosystem. But in the 1980s, the use of salmon in sushi became an overnight standard pushed by a Norwegian seafood campaign. The resulting enthusiasm for salmon exacerbated pre-existing pressure on wild populations.

While salmon had been a staple in the diets of a very small portion of the world living around northern seas, it suddenly became “essential” to the entire global seafood market. The northern commercial fishermen catching these salmon to meet consumer demand didn’t see themselves as part of an unsustainable practice, but rather as part of strong fishing lineages core to the cultural identities of the North Atlantic.

HISTORIC RANGE OF ATLANTIC SALMON

Atlantic Salmon spend most of their lives at sea, feeding on a variety of species. Their primary feeding grounds are located in the North Atlantic Ocean, off the coasts of Greenland and the Faroe Islands. These areas are rich in plankton, small fish, and crustaceans, which provide essential nutrients for salmon growth. During their feeding migrations, salmon often travel long distances, crossing vast expanses of ocean.

Orri Vigfússon was an Icelandic businessman, conservationist, and avid angler who had witnessed the collapse of the herring fishery during his youth in a fishing village. He observed the plummeting salmon returns on Iceland’s famous rivers and went directly to the source. Meeting with Icelandic and Greenlandic commercial fishermen—sometimes even boarding their boats at sea—he brokered agreements to decrease or eliminate the commercial salmon catch while simultaneously compensating fishermen and transitioning them to more sustainable fisheries. His novel approach worked and resulted in the founding of NASF. Total catch in these regions fell sharply or ended altogether, saving hundreds of thousands of salmon across the North Atlantic. As a result, Orri is credited with saving Atlantic salmon from extinction across the entire Global North.

However, Orri Vigfússon’s work to save Icelandic salmon was far from over. New threats and challenges arose, again decimating wild salmon stock. The big offenders this time were industrial plants polluting major spawning rivers and commercial open-net pen fish farms, owned by Norwegian corporations. Vigfússon died in 2017, and to carry on his work, NASF was revitalized.

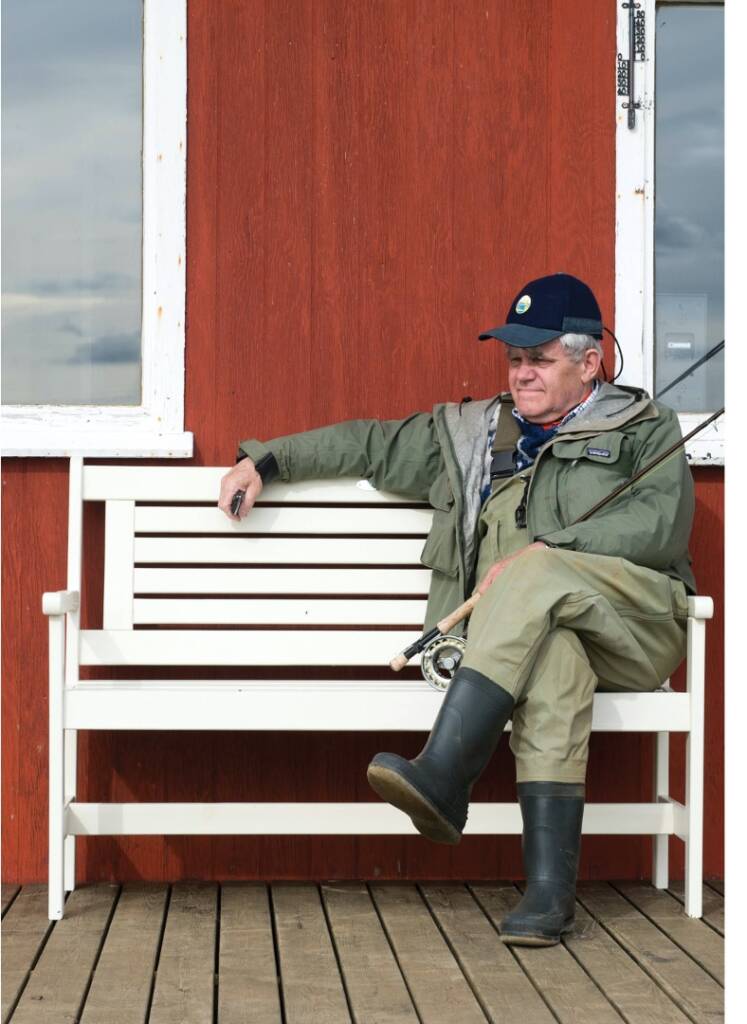

ORRI VIGFÚSSON, ICELANDIC BUSINESSMAN AND VANGUARD SALMON CONSERVATIONIST

Vigfússon received numerous awards for his salmon conservation efforts, among them medals of honor from the Icelandic, Danish, and French governments, as well as recognition from Time Magazine and The Economist. In 2007, Vigfússon received one of the most respected environmental prizes in the world from Price Charles, the Goldman Environmental Prize, for his battle to save endangered species.

Photo: North Atlantic Salmon Fund

While the industries dumping waste into rivers were brought to heel through regulation, Norwegian commercial salmon farming was another kind of beast entirely, a deeply rooted one, it turned out. To understand the entanglement of commercial salmon farming in Iceland, one must turn back the page to the 1960s, in Norway. At that time along Norway’s coasts, a new kind of aquaculture was born. Instead of catching wild salmon en masse, farmers could manage the supply and influence the demand, supplying the global market and, in theory, supporting rural fjord communities.

Salmon farm mega-corporations—usually based in Norway or Canada—have in the late 20th and 21st centuries expanded to coastlines along Scotland, Iceland, Washington State, Chile, New Zealand, and other locations. The practice spread to Iceland in the early ‘60s. At that time, the Icelandic Salmon Dispatch Station, owned by the government, started producing salmon smolts (juveniles) near Reykjavík. The smolts were released into the ocean, and the salmon would return to the station one or two years later, where they were caught in traps and harvested. The open-net pens came later and took several attempts to establish in earnest. The industry really took root in 2012 and saw significant growth around 2016.

The industry has continued to expand nearly every year since, except for 2022 and 2023, which saw declines in total production due to mass die-offs and biological issues (not because the industry shrank). Norwegian companies have consistently owned or controlled the industry in Iceland to some extent. Iceland’s open-net salmon farming industry is small compared with Norway’s, which produced 1.5M tons in 2021, or Scotland’s, which produced 205,000 tons. But it grew from under 4,000 tons in 2014 to 45,000 tons in 2021 (Figure 1). With the farms have come well-documented problems.

One major issue is animal and environmental health. One pen can hold 100,000 to 200,000 salmon. In the wild, salmon carry some sea lice, a small crustacean that latches into the scales. But in cramped quarters, sea lice outbreaks become a constant threat. When salmon become infested with the lice, they are literally eaten alive, creating the melted flesh appearance often used to illustrate the problem. To suppress outbreaks, salmon farmers throw a cocktail of heavy pesticides over the pens. These chemicals kill not only the sea lice, but any and all crustaceans in the water and across the sea floor—shrimp, lobsters, crabs, and others. The lice become resistant to treatments; newer and stronger concoctions must be applied. A vicious cycle. Beneath open-net pens, biologists and activists have documented “dead zones,” lifeless sea floors covered in bacterial mucus from all the fish waste and associated chemicals.

The industry solution to this never-ending cycle of chemical applications has been to introduce “cleaner fish” to the pens, such as puffer fish, which in the wild pick pests off other fish in a symbiotic relationship. The issue is packing in the necessary volume of puffers with those hundreds of thousands of salmon. The cleaner fish die by the thousands daily, plucked belly-up from the pens. Beyond questions of health and animal welfare, is the issue of genetic contamination in wild stock.

“Farmed salmon have now been bred selectively for six decades. Much like domestic livestock on land, the traits preferred for captive rearing are often quite the opposite of those that ensure survival in the wild,” explained Friðriksson. “Lab-bred salmon are genetically designed to grow as fat as possible as quickly as possible. Whereas a wild salmon might take years to reach peak size, a farmed salmon will reach that size (or often larger) in half the time. And the most dangerous part is that these farm fish don’t have a home river, but they still have instincts, including a drive to breed.”

When farmed salmon escape, they find their way into rivers and breed with wild stock, thereby dumbing down the wild species and dulling those traits that support survival in the wild. Studies have proven interbreeding between farmed and wild fish produces offspring that mature faster and younger, undermining the ability of the species to reproduce and survive in open water. To make matters worse for Icelandic salmon, the farmed salmon here are of Norwegian origin, further increasing the genetic difference from native wild salmon. (The irony here is that in Norway, it is prohibited to farm salmon from any other location.) Escapes are more common than the industry would like local citizens, governments, and consumers to believe. But the evidence arrives annually in spawning rivers anywhere that Atlantic salmon are farmed nearby.

While the cases of disease, pollution, and genetic contamination speak for themselves, the industry continues to cling to false narratives, namely stories around global hunger and rural livelihoods. To grow salmon in open-net pens, the fish must be fed protein and fatty acids, meaning, they must eat fish as they would in the wild.

“These companies claim that they are feeding a hungry world and taking pressure off wild stocks, but they’re not,” emphasized Friðriksson. “They’re destroying the wild salmon’s capability to do what it has done for the last 10,000 years. The only reason you can buy salmon globally is because this industry has marketed it as a healthy and necessary product. But look at what this industry is doing to hungry people in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).”

DISEASE, DEFECTS, AND ENVIRONMENTAL DEVASTATION

Crowded conditions in open-net pens promote sea lice infestations and other diseases which kill farmed fish. These maladies, along with genetic weaknesses, are spread to wild populations that combine into contact with pens or escaped fish in spawning streams.

Wild fish are caught off the coasts of LMIC nations and then ground into an oily fish meal to feed farmed salmon in the Global North. These fish meal species are perfectly edible fish that have long provided a protein base and income for coastal communities.

Friðriksson explained, “Salmon raised on fish harvested from another part of the world are ultimately a product that only a small portion of the world can afford to purchase and eat. Food is taken away from people who need it and turned into a luxury product that nobody truly needs.”

Along with the claims of ending global starvation, salmon farm corporations also make a rural livelihoods argument, asserting that they provide vital jobs in remote fjords. However, a 2023 study by the Icelandic Economy Institute showed 330 people employed annually by the industry and of those, 25% were migrant workers. In 2022, open-net pen salmon farming (ONP) contributed a meager 0.3% to the factor income of the entire Icelandic economy.

But these corporations also know how to exert political influence, employing local mayors or recruiting high-ranking officials, some in Iceland’s parliament. In addition to holding influence, the industry is self-regulated. They are accountable for hiring their own inspectors to ensure aquaculture operators are following protocols.

“The Westfjords, where salmon farming has taken hold in Iceland, have historically experienced population loss, with serious boom and bust cycles related to unsustainable industries. These practices hurt tourism, which could be a far greater economic generator. We see fish farming as putting all the eggs in one basket and then stepping on the basket,” elaborated Elias Thorarinsson, project manager at NASF. “We see other solutions, such as land-bound aquaculture. Right now, restaurants in Reykjavík only offer salmon raised on land on their menus. We live in a post-Covid world. People can live remotely and make a living. We don’t need to be yoked to these unsustainable practices.”

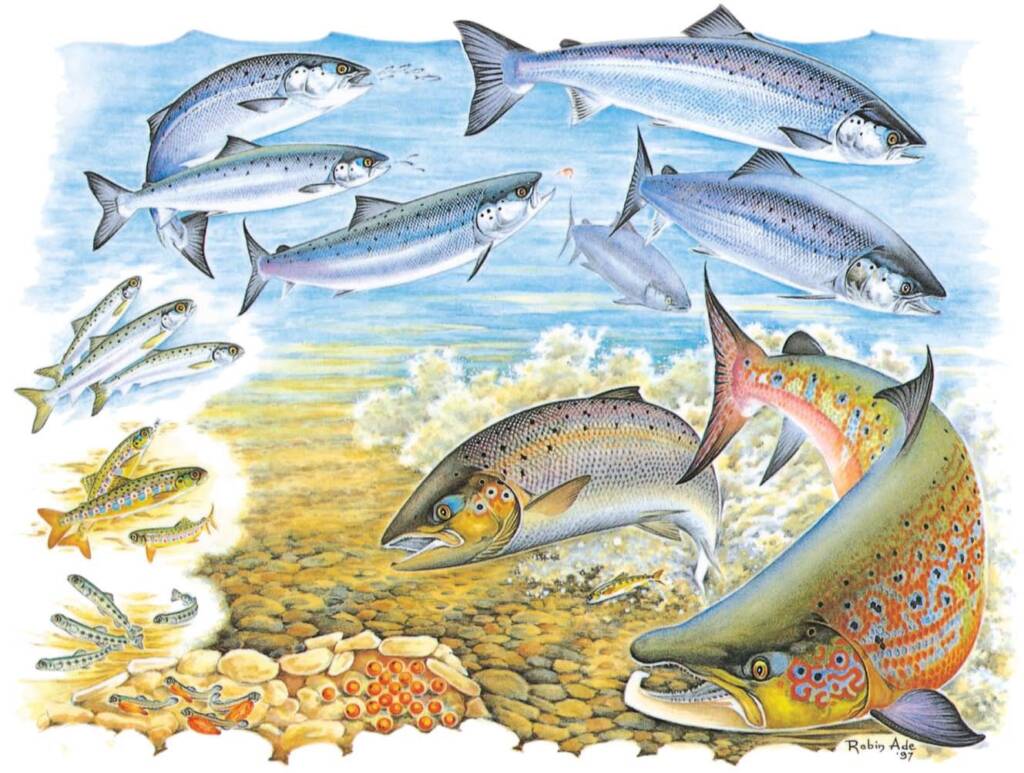

LIFE CYCLE OF WILD ATLANTIC SALMON

The life cycle of a wild slmon is the result of thousands of years of evolution. These fish grw to survive in specific and freshwater habitats at key points in their development.

Courtesy: Atlantic Salmon Trust / Robin Ade.

Wherever the open-net pens are found, wild stocks inevitably take a hit. Combine the deleterious impacts of salmon farming with the broader challenges of climate change, pollution, and dams, and wild salmon face serious challenges to survival. But the tide might be turning for good, even in the birthplace of the practice of open-net pen aquaculture.

In summer 2024, Norway’s historic salmon rivers experienced disastrous returns. So bad were the salmon runs that rivers were shut down for fishing. Lodge owners and farmers dependent on annual angling income were given four days’ notice that they couldn’t open their waters to fishing, a major blow to the recreational economy. While Norway’s disastrous spawning season might incentivize their public, Icelanders are already firmly taking a stand.

In August 2023, thousands of farmed salmon escaped from an open-net pen located on Patreksfjörður, located on the Westfjords 30 minutes from Bíldudalur and The Sea Monster Museum. Locals jumped into frigid waters to intercept the escaped fish at fish ladders and other key catch points. Escaped fish were caught in at least 32 rivers across Northern Iceland and the total number escaped was estimated at 3,500 fish. This was nothing compared to other breaches. In 2021, at least 81,000 fish escaped from a different farm on the Westfjords, for which the company was heavily fined for not reporting the escape (yet permitted to continue operations). After the 2023 breakout, Icelanders protested.

“With a total population of roughly 350,000 people, surveying Icelandic opinion is relatively easy,” said Thorarinsson. “Seventy percent of our public is firmly against salmon farming. We see what’s happened in Norway and Scotland. We see what’s happening here and a majority of the country is unified in moving on and finding sustainable solutions.”

This public dissent was channeled into a major petition effort in 2024. The “Let’s Undo This” campaign led by NASF Iceland (and with the support of key conservation partners like Icelandic Wildlife Fund and Vala Arnadottir) has garnered nearly 50,000 signatures from across Iceland and around the world, calling on Icelandic politicians to enact a ban on open-net pen salmon farms and create sustainable solutions during the 2024/25 parliamentary session.

MARCHING FOR SALMON

Through Iceland is now know for its pacifist stance and is the only NATO country without a standing military, fierce debates rage over fish. In Fall 2023, farmers and landowners from across the country converged at Austurvöllur Square in Reykjavik to protest open-net pen farming. Fishermen, biologists, and others spoke to the crowd. Icelanders are fighting to protect what they see as an integral part of their cultural heritage.

Photo: Siljurjon Ragnar

“The overwhelming number of signatures collected through the ‘Let’s Undo This’ campaign is a powerful testament to the growing public demand for change,” Thorarinsson elaborated. “Tens of thousands of voices from Iceland and around the world are calling for a ban on unsustainable salmon farming practices. This movement has become one of the largest signature-gathering campaigns in Iceland’s history, clearly showcasing the collective will to protect our natural environment and push for sustainable solutions. Now, it is in the hands of the Icelandic parliament and those in power to listen to the will of the people and enact the necessary changes.”

Fish are a pillar of Icelandic identity, even the basis of their economy. In medieval Iceland, fiskur (fish) was a value standard. An old Icelandic saying goes, “That doesn’t add up to many fish,” meaning something is of little value or poor quality. The open-net pen industry clearly doesn’t add up to many fish. And for today’s Icelanders, the real measure of value lies in preserving their natural heritage and wild salmon stocks for future generations.

As the country gears up for a new chapter in its long history of fisheries management, the question remains: Will Iceland become a world leader in sustainable fish-farming practices, or will it fall prey to the same mistakes that have decimated wild Atlantic salmon populations elsewhere?

LET’S UNDO THIS

It doesn’t take an advanced anthropology degree to understand that fish (fiskur) are inextricably woven into the Icelandic psyche and identity. Look at the island’s diet, geographic names, and earliest recorded ballads, and you’ll find constant references to various fish species, especially to lax—salmon. When farmed salmon escape, citizens step forward to take action however they can. Here, volunteers remove escaped farmed salmon from key wild salmon spawning streams.

Photo: Elias Petur Vidfjord Thorarinsson

LET ’S UNDO THIS

It doesn’t take an advanced anthropology degree to understand that fish (fiskur) are inextricably woven into the Icelandic psyche and identity. Look at the island’s diet, geographic names, and earliest recorded ballads, and you’ll find constant references to various fish species, especially to lax—salmon. When farmed salmon escape, citizens step forward to take action however they can. Here, volunteers remove escaped farmed salmon from key wild salmon spawning streams.

WHAT YOU CAN DO

1. Sign the “LET’S UNDO THIS” petition.

2. At the grocery store and restaurants, either buy sustainably caught wild salmon or salmon raised on land. Avoid salmon farmed in open-net pens in the ocean. Choose sustainably caught wild salmon options whenever possible.

3. Support the efforts of NASF HERE.

4. SPREAD THE WORD.